What is Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory?

Erik Erikson's theory of psychosocial development offers a comprehensive framework for understanding human growth across the entire lifespan. Departing significantly from purely psychosexual interpretations of development, Erikson posited that individuals navigate a series of distinct social and emotional challenges from infancy through old age.

Successfully resolving these crises contributes to the formation of a healthy personality and the acquisition of fundamental virtues. This article explores the core tenets of Erikson's influential model, delving into each of his eight stages and examining how his work has profoundly altered our perspective on development, particularly in the context of childhood.

Background and Context: Erik Erikson's Life and Influences

Born in Germany in 1902, Erik Erikson's own life journey, marked by questions of identity and belonging, arguably shaped his theoretical perspectives.

Trained in psychoanalysis in Vienna, he worked closely with Anna Freud, initially grounding his ideas in Freudian principles. However, his experiences immigrating to the United States and working with diverse cultural groups, including the Sioux and the Yurok, broadened his view beyond individual psychology to encompass social and cultural factors.

Psychoanalytic Roots and Cultural Perspective

Erikson's theory emerged from the psychoanalytic tradition, retaining concepts such as the unconscious, ego development, and the influence of early experiences. However, he expanded upon Freud's model by incorporating the impact of the social environment and cultural context on development.

He saw the ego not just as a mediator between id and superego, but as a constructive force actively engaging with the world and resolving conflicts.

Shift from Psychosexual to Psychosocial

The most significant departure from Freudian theory was Erikson's shift from a psychosexual emphasis to a psychosocial one. While acknowledging the biological drives Freud highlighted, Erikson argued that personality development is driven by social interactions and the individual's attempt to become a functioning member of society. Development, in his view, was a negotiation between internal psychological needs and external social demands across the entire lifespan, not solely fixated on early childhood sexual stages.

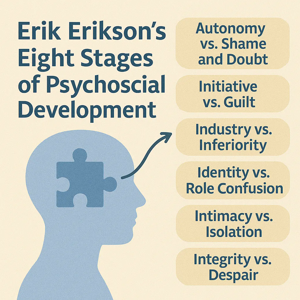

Overview of the Eight Stages of Development

Erikson's theory rests on several fundamental concepts that differentiate it from earlier developmental models. These include the idea of the psychosocial crisis at each stage, the resulting ego strength or virtue, and the extension of development across the entire life course.

The Psychosocial Crisis

At the heart of Erikson's theory is the concept of the psychosocial crisis. Each of the eight stages is characterised by a specific conflict or challenge that the individual faces.

This crisis involves a tension between two opposing tendencies, typically represented as a positive and a negative outcome. Successful navigation of the crisis involves finding a balance between these poles, leading to healthy development.

Failure to adequately resolve a crisis can impact development in later stages.

Ego Strength and Basic Virtues

Successful resolution of each psychosocial crisis leads to the development of an ego strength or basic virtue.

These virtues represent positive qualities or capacities that the individual gains, equipping them to face subsequent challenges. For example, resolving the first stage crisis builds hope, while resolving the adolescent crisis leads to fidelity (Agrawal, 2014)

These virtues are cumulative, with the strengths gained in earlier stages providing a foundation for successful navigation of later ones.

Life-Span Perspective

A key innovation of Erikson's theory was its extension of development beyond childhood and adolescence to encompass adulthood and old age. He argued that personality continues to evolve throughout life, with distinct challenges and opportunities for growth at every phase.

This life-span perspective contrasted sharply with theories that viewed development as largely complete by early adulthood.

The Early Stages: Foundations of Personality (Infancy to Preschool)

The initial stages of Erikson's model lay the crucial groundwork for later personality development. Experiences in these early years shape fundamental beliefs about the world and one's place within it, heavily influenced by primary caregivers.

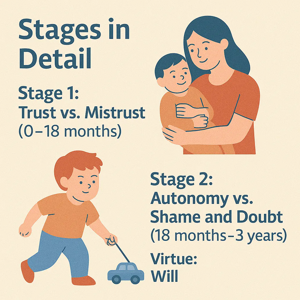

Stage 1: Trust vs. Mistrust (Birth to 18 months)

The first psychosocial crisis occurs during infancy, centering on the development of trust. Infants are entirely dependent on their caregivers for survival and comfort.

When caregivers are consistently responsive, reliable, and attentive to the infant's needs (feeding, changing, comforting), the infant develops a sense of basic trust in the world and in others. This secure attachment provides a foundation of security.

Conversely, inconsistent, neglectful, or unresponsive care leads to a sense of mistrust, making the infant feel anxious, insecure, and apprehensive about the world.

The successful resolution of this stage, marked by a balance where trust predominates, yields the virtue of Hope – a belief that even when needs are not perfectly met, they will eventually be satisfied and that there is goodness in the world.

Parental influence during this stage is pivotal; a trusting and supportive relationship helps the child overcome the crisis and establish the virtue of hope (Verma, 2013).

Stage 2: Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (18 months to 3 years)

As toddlers gain greater physical mobility and cognitive abilities, they confront the crisis of Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt.

This stage focuses on developing a sense of personal control over physical skills and a sense of independence. Children begin to assert their will, make choices, and explore their environment. Opportunities for exploration, making simple decisions, and mastering basic tasks like walking, feeding, and toileting contribute to a sense of autonomy.

Supportive caregivers encourage this exploration within safe boundaries. Overly restrictive, critical, or punishing parenting can lead to feelings of shame and doubt about one's abilities and self-control.

If parents force a child into certain behaviours or prevent appropriate exploration, the child may struggle to reach autonomy achievement later (Verma, 2013).

The successful negotiation of this stage, achieving a balance where autonomy is dominant, results in the virtue of Will – the capacity to make choices and exercise self-control.

Stage 3: Initiative vs. Guilt (3 to 5 years)

During the preschool years, children's social world expands, and they face the crisis of Initiative vs. Guilt.

Children become more purposeful and assertive. They take initiative in planning and carrying out activities, exploring social roles through play, and asking questions to understand the world.

Encouraging this initiative, supporting their curiosity, and allowing them to engage in imaginative play helps them develop a sense of purpose. However, if children are overly criticised, controlled, or discouraged from exploring and taking initiative, they may develop feelings of guilt about their desires and actions.

This can lead to a reluctance to take risks or pursue goals. While initial substance use in this age group may impede psychosocial development, significant gains in initiative are seen in children who do not initiate substance use (Jones, 2011).

The successful resolution of this stage, with initiative outweighing guilt, leads to the virtue of Purpose – the capacity to initiate activities and pursue goals.

Stage 4: Industry vs. Inferiority (6 to 11 years)

As children enter school, the crisis of Industry vs. Inferiority becomes central.

The focus shifts from play to work and accomplishment. Children learn academic skills and develop social skills by interacting with peers and teachers. Success in schoolwork, extracurricular activities, and social interactions fosters a sense of competence and industry – the feeling that one is capable and can contribute.

Recognition from teachers and parents for efforts is important. Conversely, repeated failures, lack of encouragement, or negative comparisons to peers can lead to feelings of inferiority – a belief that one is inadequate or incompetent.

Children who achieve significant gains in psychosocial development, including industry, are less likely to initiate substance use compared to those who show declines in industry (Jones, 2011).

The successful resolution of this stage, where industry prevails, cultivates the virtue of Competence – the ability to apply skills and intelligence to tasks.

Stage 5: Identity vs. Role Confusion (12 to 18 years)

Adolescence marks the critical stage of Identity vs. Role Confusion.

Teenagers grapple with questions of "Who am I?" and "Where do I fit in?" They explore various roles, beliefs, and goals, attempting to integrate their past experiences with future aspirations to form a coherent sense of self.

This exploration involves experimenting with different identities related to career, religion, politics, and relationships. Support for this exploration from parents and society is crucial (McQueen, no date).

Successful negotiation leads to a strong sense of personal identity, providing a stable foundation for adulthood. Conversely, failure to explore or integrate these aspects results in role confusion, leaving the adolescent unsure of their place in the world. Identity development during this period is linked to healthy development and reduced risk behaviours (Brittian, 2011).

Some theoretical work suggests early substance use may impede identity development (Jones, 2011).

Parental influence, particularly allowing appropriate autonomy, is pivotal for a child reaching identity achievement (Verma, 2013). The concept of identity formation in adolescence endures as a key theoretical contribution, though contemporary perspectives consider expansions in light of technological advances and positive youth development.

University settings are recognised as environments where psychosocial development, including identity formation, inevitably occurs, and structuring such environments optimally benefits students (Marcia, 2009). Research connects identity status to academic achievement, suggesting higher status aligns with better performance (Flammia, no date).

Measures based on Erikson's theory are used to assess identity status, including in specific domains like religious identity (Stojkovic, Dimoski and Miric, 2020). Chickering's theory, which builds on Erikson's work, also identifies establishing identity as a key vector of college student development, involving comfort with various aspects of self and self-acceptance .

A sense of personal "authenticity" rooted in self-values, relevant to identity, can conflict with the need for that identity to be recognised within a collective (Scully, 2014). The successful resolution of this stage yields the virtue of Fidelity – the ability to commit to others and to one's own beliefs and values.

The Adult Stages: Contribution and Reflection (Young Adulthood to Late Life)

Erikson's theory uniquely details the challenges and developments faced throughout adulthood, highlighting the ongoing nature of psychosocial growth.

The following stages all occur in adulthood and while not relevant to the purpose of this website are include in brief to provide a more complete view of Erikson’s theory.

Stage 6: Intimacy vs. Isolation (19 to 40 years)

Following the establishment of identity, young adults face the crisis of Intimacy vs. Isolation.

This stage centres on forming close, committed relationships with others. Building intimate relationships requires vulnerability, mutual trust, and a willingness to share one's life with another.

Success in this stage involves developing deep friendships and potentially a romantic partnership, leading to a sense of connection and belonging. Failure to form meaningful connections, perhaps due to unresolved identity issues or fear of vulnerability, results in isolation and feelings of loneliness.

The successful resolution of this stage, with intimacy prevailing, produces the virtue of Love – the ability to form close, committed relationships with others.

Stage 7: Generativity vs. Stagnation (40 to 65 years)

During middle adulthood, the primary challenge is Generativity vs. Stagnation.

Generativity involves a concern for establishing and guiding the next generation, contributing to society, and feeling productive. This can manifest through parenting, mentoring, teaching, contributing to community, or creative work.

People strive to leave a positive legacy. Stagnation, the opposite, occurs when individuals feel disconnected from others and society, unproductive, and self-centred. They may feel a lack of purpose or meaning in their lives.

The successful resolution of this stage, where generativity dominates, yields the virtue of Care – a commitment to nurture and guide future generations.

Stage 8: Ego Integrity vs. Despair (65 years onwards)

The final stage of psychosocial development is Ego Integrity vs. Despair, faced in late adulthood.

As individuals reflect on their lives, they assess whether their life has been meaningful and fulfilling. Ego integrity involves a sense of wholeness and satisfaction, accepting one's life choices and experiences, including regrets, as part of a unique and valuable journey. There is a sense of peace and wisdom.

Conversely, despair arises from regret over missed opportunities, unresolved conflicts, and a feeling that life has been wasted. This can lead to bitterness, depression, and a fear of death.

The successful resolution of this stage, with ego integrity prevailing, produces the virtue of Wisdom – a detached concern with life itself in the face of death.

Application in Child and Adolescent Development

Erikson's psychosocial theory has had a profound and lasting impact on the field of developmental psychology and beyond, significantly altering how we perceive human growth.

Broader View Beyond Childhood

By extending the developmental framework across the entire lifespan, Erikson challenged the traditional view that personality is largely fixed in childhood. He highlighted that growth and change are continuous processes.

Emphasis on Social and Cultural Factors

His theory underscored the critical role of social interaction, cultural norms, and societal expectations in shaping personality development, moving beyond a purely internal or biological focus.

Influence on Developmental Psychology and Practice

Erikson's stages provide a widely used framework for understanding typical developmental challenges at different ages. His concepts have influenced parenting practices, educational approaches, and counselling methods by highlighting the specific social and emotional needs individuals face at various life stages (Marcia, 2009)(Verma, 2013).

The theory helps identify potential points of difficulty or crisis.

Strengths and Criticisms of Erikson’s Theory

While highly influential, Erikson's theory also faces critiques, including its limited empirical testability compared to some other psychological models, the perceived universality of the stages across all cultures, and a perceived bias towards Western, male experiences.

However, many core concepts, particularly identity development in adolescence, remain highly relevant and continue to be explored and expanded upon in contemporary research . Its application in educational settings, for instance, demonstrates its continued practical value (Marcia, 2009).

Relevance in Modern Education and Parenting

Although Erikson's theory spans the entire life course, it offers particularly valuable insights into child development by providing a structured view of the social and emotional milestones individuals must achieve in the early years.

His focus on the interaction between the developing individual and their environment helps illuminate the complexities of growing up.

Understanding Developmental Milestones and Challenges

Erikson's first four stages provide a clear roadmap of the core social and emotional challenges faced from infancy through the school years: establishing trust, developing autonomy, taking initiative, and building competence.

Understanding these crises helps parents, educators, and clinicians anticipate typical developmental hurdles.

Applications in Parenting, Education, and Counselling

The theory offers practical guidance. Parents understand the need for consistent care to foster trust, allowing toddlers safe exploration for autonomy, and encouraging purposeful play for initiative.

Educators can create environments that support children's sense of industry.

Counsellors use the framework to assess where a child might be struggling and develop interventions to support healthy resolution of the psychosocial crisis for their age (Verma, 2013).

Limitations when Focused Solely on Childhood

While powerful for understanding early years, viewing Erikson's theory solely through the lens of childhood development misses its crucial lifespan perspective. The challenges faced in childhood lay the foundation for adulthood, and issues unresolved in early stages can resurface later in life, demonstrating the interconnectedness of all eight stages.

Conclusion: The Enduring Relevance of Erikson's Framework

Erik Erikson's psychosocial theory remains a cornerstone of developmental psychology.

By presenting development as a series of social challenges spanning the entire life course, he provided a richer, more dynamic understanding of how individuals grow and form their identities.

His emphasis on the interplay between the individual, society, and culture offered a vital counterpoint to purely biological or psychosexual models. While subject to critique, the framework of psychosocial crises and resulting virtues continues to provide valuable insights for researchers and practitioners alike, helping to navigate the complexities of human growth from the earliest moments of life through old age.

It underscores that development is a continuous process of adaptation, learning, and negotiation within the social world.