Introduction: Why Children’s Needs Must Come First

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, first proposed in 1943, provides a foundational framework for understanding human motivation as a progression of essential requirements (Gladden, 2020).

According to this model, individuals must meet lower-tier needs—such as physiological and safety requirements—before higher-level needs like self-esteem or self-actualisation can be effectively pursued.

When applied to child development, Maslow’s theory offers valuable insight into how unmet needs can significantly impact a child’s capacity to learn, form relationships, and develop a stable sense of self.

For professionals working with children, particularly in educational or therapeutic settings, recognising and responding to these needs is critical to promoting holistic well-being and engagement.

This discussion will examine the practical application of Maslow’s hierarchy in child-centred practice, with a focus on how systemic, relational, and cultural dynamics influence the extent to which children’s needs are met.

What Is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Why It Matters for Children

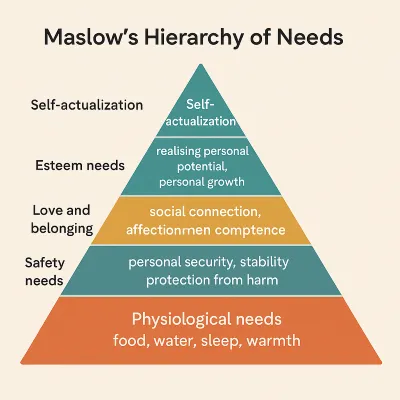

Maslow’s hierarchy outlines five tiers of human needs, commonly depicted as a pyramid.

- At its base are physiological needs—fundamental biological requirements such as food, water, sleep, and warmth.

- Once these are adequately met, safety needs emerge, encompassing personal security, stability, protection from harm, and a predictable environment.

- The third tier involves love and belonging, referring to meaningful social relationships, emotional connection, and a sense of acceptance within groups.

- Esteem needs follow, including self-respect, competence, autonomy, and recognition from others.

- At the apex lies self-actualisation—the intrinsic drive to fulfil one’s potential, pursue personal growth, and engage in meaningful activities.

(Gladden, 2020)

This structured progression underscores the interdependence of human needs: when foundational needs are unmet, higher-order psychological growth is often compromised.

Understanding this hierarchy provides a useful scaffold for professionals seeking to interpret behaviour, engagement, and wellbeing in children through a needs-focused lens.

Why Meeting Children’s Needs Is Essential for Learning and Development

A child’s ability to engage in learning, form relationships, and express individuality is fundamentally shaped by the extent to which their basic needs are met. Maslow’s hierarchy underscores that without the fulfilment of physiological and safety needs, higher-order capacities—such as attention, memory, and emotional regulation—are significantly compromised (Main and Whatman, 2023). Likewise, unmet needs for belonging and esteem can erode confidence, diminish motivation, and obstruct peer integration (Main and Whatman, 2023).

Educational efficacy, therefore, must extend beyond curriculum delivery to embrace a holistic view of the child. For practitioners, this means recognising behavioural or academic difficulties not solely as performance issues, but as possible indicators of unmet foundational needs. Supportive, child-centred interventions that address these needs are not peripheral—they are essential to enabling academic progress, healthy development, and long-term resilience.

How Maslow’s Hierarchy Applies to Work with Children

Supporting Children’s Basic Needs: Food, Sleep, and Safety in School

Physiological needs for children include adequate nutrition, hydration, rest, and a physically comfortable environment. Safety needs extend beyond physical protection to encompass emotional security, predictability, and freedom from fear. In educational settings, this translates to providing nutritious meals, clean drinking water, appropriate room temperatures, and consistent routines. A child experiencing hunger, fatigue, or insecurity is physiologically and emotionally unprepared to engage in learning (Main and Whatman, 2023). Meeting these basic conditions is not optional—they are non-negotiable foundations for educational participation.

How Unmet Needs Affect Children’s Behaviour and Emotions

When basic needs are unmet, children often display signs through behaviour and affect. Hunger can lead to poor concentration, irritability, or withdrawal (Main and Whatman, 2023). Chronic fatigue undermines cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and resilience. Similarly, a lack of perceived safety—stemming from chaotic home lives or unpredictable school environments—may manifest as anxiety, hypervigilance, aggression, or emotional shutdown (Main and Whatman, 2023). These are not simply disciplinary challenges, but indicators of deeper unmet needs, which must be addressed through informed, compassionate responses.

Spotting and Responding to Signs of Unmet Needs in Children

Practitioners can identify unmet needs by observing patterns in a child's physical appearance, energy, and behaviour. A child who arrives consistently late, appears unwashed, or hoards food may be experiencing deprivation. Hypervigilance, separation anxiety, or explosive behaviour can signal unmet safety needs. Addressing these requires targeted strategies—such as offering breakfast provision, creating calm spaces for rest, or engaging with families to explore support options. Schools also play a preventative role by maintaining predictable routines, clear expectations, and emotionally safe environments (Main and Whatman, 2023).

Helping Children Feel Valued, Connected, and Confident

Once basic needs are met, the focus shifts to relational and psychological growth. Love and belonging involve feeling cared for, accepted, and part of a community (Dimitrellou and Hurry, 2018). Esteem needs include a sense of personal value, capability, and external recognition (Main and Whatman, 2023). These levels are crucial in shaping a child's self-concept and their ability to engage confidently with others.

Building Positive Relationships and Peer Belonging in School

Secure attachments form the blueprint for all future relationships. In school, nurturing teacher-pupil relationships are central to building trust and emotional security (Main and Whatman, 2023). Peer dynamics also matter—social acceptance often predicts a child’s classroom engagement and emotional resilience (Dimitrellou and Hurry, 2018). Children with SEMH or behavioural challenges frequently report feeling disconnected from peers and unsupported by staff. Teachers can counteract this through structured group work, restorative approaches, and inclusive classroom cultures that value all contributions (Main and Whatman, 2023).

Boosting Children’s Self-Esteem and Motivation through Practice

Self-esteem flourishes when children experience success, feel competent, and receive genuine recognition. Educators can build this through scaffolded tasks, meaningful praise, and opportunities for responsibility. Leadership roles, peer mentoring, and creative contributions foster a sense of pride and purpose. Such practices support intrinsic motivation and help children internalise a growth mindset—perceiving effort and persistence as pathways to achievement (Society for Research in Child Development, 2007).

Supporting Children’s Potential: What Self-Actualisation Looks Like

At the pinnacle of Maslow’s model lies self-actualisation—the fulfilment of one’s potential and the pursuit of meaningful expression (Hanaba, 2018). For children, this means being given the autonomy to explore interests, solve problems, and contribute in personally meaningful ways. A needs-led environment makes this possible by removing the stressors that inhibit exploration and self-direction.

How to Recognise Self-Actualisation in Children

Self-actualising children tend to be intrinsically motivated, curious, and confident in tackling unfamiliar challenges. They embrace mistakes as learning opportunities and demonstrate creativity, critical thinking, and ethical reasoning (Hanaba, 2018). These qualities are nurtured, not innate—emerging when children are supported, trusted, and given freedom to develop personal agency.

Practical Ways to Help Children Thrive and Find Their Voice

To foster self-actualisation, educators must provide choices, encourage inquiry, and design tasks that allow for personal expression. Open-ended learning, self-directed projects, and critical dialogue create conditions where children can think deeply and act authentically. Promoting self-reflection, decision-making, and collaborative problem-solving empowers children to take ownership of their learning and flourish as individuals (Main and Whatman, 2023).

Beyond the Classroom: What Shapes Children’s Needs Being Met

Systemic Barriers to Children’s Wellbeing and School Engagement

The fulfilment of children’s needs within education is not limited to individual teacher-student interactions—it is shaped by broader systemic structures. These include governmental policy, socioeconomic inequality, and institutional capacity. Recognising and responding to these influences is essential for developing equitable, effective, and sustainable support strategies.

How Poverty and Funding Inequality Impact Children’s Needs

Poverty continues to pose a significant barrier to the fulfilment of children’s basic needs. Pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds may face chronic hunger, unstable housing, and limited access to healthcare, all of which affect physiological well-being and perceived safety (Yudkin and Yudkin, 1968). In turn, schools serving these communities are often under-resourced, with reduced capacity to offer early interventions such as breakfast programmes, emotional support, or specialist provision (Tanner, 2005). This entrenches inequality, leaving foundational needs unmet and hindering sustained educational engagement (Main and Whatman, 2023).

The Role of Education Policy in Supporting Children’s Needs

Policy plays a central role in shaping how children’s needs are identified and met. Landmark developments such as the Warnock Report (1978) shifted the paradigm from a deficit-based model of special education towards a needs-based, inclusive framework. Contemporary inclusion policies continue this trajectory (Rajšli-Tokoš, 2020; Rix et al., 2013), but implementation remains inconsistent. Where policies lack adequate funding, staff training, or leadership support, their intent often fails to materialise in daily practice (Rayner, Gunter and Powers, 2002). Thus, policy reform must be accompanied by investment and workforce development to truly impact children's lived experiences.

The Practitioner’s Role in Identifying and Meeting Children’s Needs

While systems provide structure, it is the quality of day-to-day relationships that often determines whether children’s needs are recognised and addressed. Practitioners act as crucial connectors between children’s internal experiences and external support systems.

Building Trust with Children and Families: A Foundation for Support

Effective identification of need begins with trust. Children are more likely to disclose unmet needs or emotional struggles when they feel safe, respected, and genuinely heard by a trusted adult (Więcławska, 2018). Likewise, building collaborative relationships with families—grounded in mutual respect—enables practitioners to gain deeper insight into a child’s background and barriers. This partnership approach allows interventions to be tailored and family-informed.

Working Together: Why Multi-Agency Support and Reflection Matter

The complexity of many children’s needs necessitates multi-agency responses. Collaboration between educators, health professionals, social care, and mental health services ensures coordinated, holistic support (Hemingway and Cowdell, 2009). Practitioners must also engage in professional reflexivity—critically examining their own assumptions, biases, and cultural lens. This reflective practice enhances ethical, person-centred decision-making and safeguards against the misuse of power or the misreading of behaviours.

Meeting Children’s Needs in Culturally Responsive Ways

While Maslow’s model assumes universal human needs, their interpretation and fulfilment are mediated through cultural norms and expectations. Practitioners must approach need identification through a culturally informed lens to avoid misjudgement and exclusion.

Inclusive Practice: Valuing Identity and Representation

Culture influences everything from emotional expression to attitudes toward authority and education. Failing to recognise this can marginalise pupils and undermine their sense of belonging and esteem. Inclusive, culturally responsive practice involves celebrating diverse identities, using culturally relevant pedagogy, and ensuring that classroom materials reflect the lived experiences of all learners (Society for Research in Child Development, 2007). Representation fosters connection, and connection fuels engagement.

Overcoming Cultural Barriers in School-Home Communication

Cross-cultural communication can be fraught with misunderstanding. Language barriers, differing communication styles, and contrasting parental expectations around behaviour or academic success can complicate engagement (Zhou et al., 2019). Misinterpretations may lead to inappropriate labelling or support strategies. Practitioners must prioritise empathy, curiosity, and open dialogue—recognising that culturally grounded behaviours may not align with dominant educational norms, yet still reflect valid perspectives on child development and wellbeing.

Conclusion: Putting Maslow into Practice for Better Child Outcomes

What We’ve Learned: Implications for Practice and Policy

Maslow’s hierarchy remains a compelling framework for understanding the layered and interconnected needs of children in educational settings. It reinforces the principle that academic engagement cannot occur in isolation from a child’s physiological safety, emotional security, and sense of personal value. When foundational needs are unmet, children’s behaviour, regulation, and learning are significantly disrupted, leading to disengagement and reduced life chances (Main and Whatman, 2023).

Systemic inequities—such as socioeconomic disadvantage and uneven policy implementation—compound these challenges, while relational and cultural dynamics play a crucial role in whether needs are recognised and addressed. Meeting the full spectrum of children’s needs requires a systemic, relational, and culturally responsive approach grounded in collaboration, equity, and reflective practice.

Recommendations: Creating Schools Where All Children Can Thrive

To enhance environments that foster holistic child development, several recommendations emerge:

- Develop Integrated Support Systems

Establish strong multi-agency partnerships involving education, health, social care, and voluntary sectors. These should offer wraparound support such as school-based mental health services, breakfast clubs, and designated safe spaces (Hemingway and Cowdell, 2009). - Embed Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Across the Curriculum

Systematically teach SEL competencies—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making—as core to educational outcomes, not peripheral (Main and Whatman, 2023). - Adopt Relationship-Centred Pedagogy

Build classrooms around emotional safety and relational trust. Strong teacher-student and peer relationships promote belonging, engagement, and positive self-concept, especially for pupils with SEMH needs (Main and Whatman, 2023; Dimitrellou and Hurry, 2018). - Invest in Professional Development

Provide ongoing training in trauma-informed practice, cultural humility, and child development. Equip staff to identify and respond to unmet needs with confidence, empathy, and nuance (Main and Whatman, 2023). - Advocate for Equitable Funding and Resourcing

Policy must address structural inequalities by directing increased funding, specialist staff, and infrastructure to schools serving high-need communities (Yudkin and Yudkin, 1968). - Promote Autonomy, Voice, and Self-Actualisation

Offer opportunities for choice, creativity, and critical thinking. Environments that support agency enable children to develop their identity, resilience, and long-term capacity for self-directed learning (Hanaba, 2018).